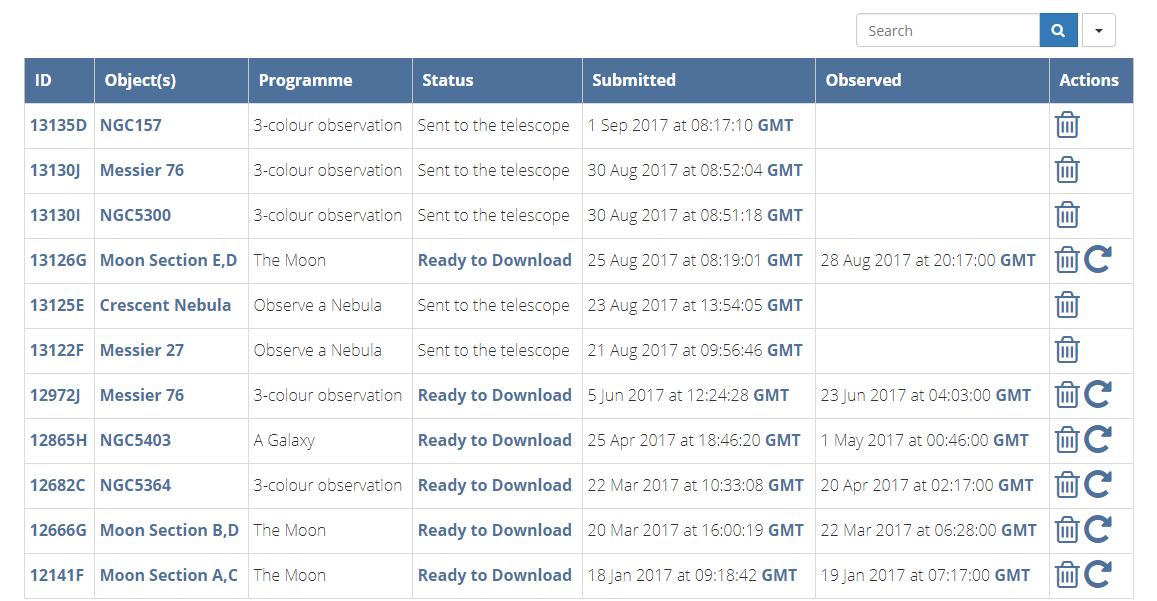

Check My Observations

Once your requests have been sent to the telescope, you can simply sit back and relax - the telescope will carry them out at the best possible time.

You can keep an eye on the status of your observations using the "My Observations" tool. Here you will be given a list of all the observing programmes that you have requested with a summary of their current status. Simply click on the Code for a particular programme to find out more details.

The Liverpool Telescope (LT) uses a sophisticated computer programme called a scheduler to make sure observations are done as soon as possible and at the best time. Any observations that you have requested will be included in this.

Telescope Management Centre

and Telescope Management Centre

The first stop for your request is the Telescope Management Centre in Liverpool. Here a computer compares your request with any other ones that have already been submitted but are not observed yet. If any are identical they are combined (this makes it easier to get your observation done as quickly as possible). It then works out a priority value for the request. The more requests that are combined together, the higher the priority, but it also gives a priority boost to users who have not made many requests.

As soon as this is done, your observation request is ready to be sent out to the observatory on La Palma to be put together with all the requests from everyone else who uses the telescope, including those from professional astronomers. This happens continuously, even during the night, so you can request observations whenever you want.

Sunset

Image by M Tomlinson/LT

Just before sunset on La Palma, one of the LT staff in Liverpool gets online to watch the telescope systems start up. They usually do not need to do anything, but it is good to have someone to check just in case. If the weather is OK, the dome of the telescope will open by itself, the staff member will log off, and the telescope will start observing. As it will still be quite bright, the telescope starts by taking observations that will be used to calibrate the observations taken during the rest of the night.

However, once it is dark enough, it can start trying to take observations for you and all the other astronomers who have made requests.

During the night

All through the night, the computers at the telescope make decisions about which observation to do next. So, whenever an observation has finished it chooses the best one to do next from the huge list of requests. It starts by working out which could be observed.

To decide if an observation is currently possible, the scheduler asks a set of questions:

- Is the object high enough above the horizon?

- Will it stay high enough all the way through observation (this depends on the exposure time)?

- Will it be possible to finish the observation before the end of the night?

- Is the sky dark enough for the needs of this particular observation?

- Is the "seeing" good enough for the observation?

- If the observation needs the very best conditions, is it a night with no cloud at all?

- If it has to be done at a special time (say at a particular point in an orbit, or when a variable star is very bright), is the time right?

Only if the answer to all of these is "yes", will it pass the request onto the next stage.

This narrows down the big list to a smaller one of all the observations that could possibly be done now. These are then ranked using a special piece of computer code called an algorithm. The observation with the highest rank is then observed and the process starts again.

The rank given to each possible observation depends on:

- Slew time: This is a measure of how far the across the sky the telescope will need to move from its current position. The less it has to move the better, as this is more efficient.

- Height above the horizon: If the object is going to be further above the horizon later in the night, it might be better to wait, so the rank number is lowered a bit until then. It does not compare it to other objects in other observations though.

- Priority: Higher priority observations are given a boost to their ranking.

- Completion: Big science projects that need lots of observations over a number of nights, or even months, are also given a bit of a boost as otherwise completing them might be difficult.

The overall rank number for each possible observation at that particular moment is then compared and the one with the highest rank is observed.

Because it starts again with the full list every time rather than planning the whole night in one go, the telescope can make observations from requests that have only just been made. This is very useful for trying to learn more about things change very quickly or unpredictably, such as exploding stars like supernovae or gamma-ray bursts. It also means that whenever you make your request - even in the middle of the night - the telescope will start trying to observe it straight away.

Sunrise

As the Sun rises, the dome closes automatically. All the data that was taken during the night is then carefully calibrated by another computer programme using the special observations taken during the night.

All observations sent from The Schools' Observatory are checked by a member of the team. Sometimes you might have been unlucky and your observation might have been taken through a small unexpected cloud, or there might have been a technical problem. This is quite rare, but if it happens we will simply send your request back to the telescope to try again.

Finally, the data files for your observation are copied over The Schools' Observatory website and are ready for you to download and explore.

Why might my observation be delayed or not completed at all?

Images: LT Webcam

Sometimes you might need to wait a while for your observation, or it might not be possible for the telescope to complete it in time for you. Because the weather is so important, patience is very important in observational astronomy, but there are a few things that might help you to understand why you might not be lucky with your observations.

Seasons

Even when you observe quite close to the equator like on La Palma, the nights are longer in winter than summer, so that might seem like a better time to observe. However, the winter weather is often worse, so it is still down to luck.

Across the sky

As the Earth spins around each day, and orbits around the Sun each year, the part of the sky that can been seen changes. To help work out if something is visible at a particular time, we use coordinates - every star and galaxy has its own coordinate which tells us where it is in the whole sky around the Earth. At any time we can use that coordinate to work out where the telescope would need to point to observe it.

There are three main things that the coordinates tell us that can be important:

- North/South: Some objects are in the sky a long way to the south of the equator can only be seen from the southern hemisphere, and so can never be observed from La Palma. Others are quite far south and so only ever get a little bit above the horizon from La Palma, making them more difficult to observe.

- Time of year: As the Earth orbits around the Sun, different parts of the night sky appear to move away from the Sun. This is, of course, the bit that is "up" during the night. So we can use the coordinate to work out when during the year an object is visible at night, and not hidden by the bright daytime sky.

- Time of night: As the Earth spins, it makes the stars look as though they move across the sky, with some rising and setting just like the Sun. Using an objects coordinate we can work out the best time each night to observe it, usually when it is high in the sky.

This is all a bit more complicated for the Moon, asteroids, and planets that are orbiting around the Sun as their coordinates do not stay the same. However, we can calculate what their coordinates are at a particular time, so we can still work out when they can be observed.

Sky Brightness

While some things in the night sky are quite bright like the Moon or some stars, many of the things we want to observe are quite faint. The fainter something is, the harder it is to observe, especially if the sky is not really dark. Fortunately on La Palma we do not need to worry about light pollution, but some other things, like twilight or the Moon, can make the sky a bit too bright to observe the faintest objects.

Twilight: Just after the Sun has set, and again as dawn is approaching, the sky gets brighter. Even when you might not be able to see the difference with your own eyes, the special cameras on the telescope can tell the difference, so for any objects that are not bright we need to avoid what is called "Astronomical Twilight".

Moon: The Moon is bright enough that it can make the whole sky glow. How bright the sky is around your object depends on the phase of the Moon (the full Moon is obviously brighter) but also how far apart the object and the Moon appear to be. For fainter, fuzzy objects like galaxies and nebulae this can be very important and often means that they cannot be observed near to full Moon.

On the left the Milky Way is visible but on the right the Moon is too bright for it to be seen.

Images from LT SkyCamA

The effect of both coordinates and sky brightess can be predicted, so they are used to make the coloured bars that you might see as you decide on your observations.

Seeing

Images: The Schools' Observatory/LT

"Seeing" is what astronomers call the "blurring" of astronomical pictures by the atmosphere. The amount of blurring changes and observations that need the sharpest possible images can only be done at certain times. The telescope measures the quality of the seeing all the time, so it will take observations that need to be good only when conditions are right. This means that requests which ask for the best conditions have more competition in the "ranking", whereas if the poorer quality is OK, then it is easier for the telescope to fit the observation in.

Long vs. Short

Observations that take a long time to carry out are harder for the telescope to fit in than those that are quick. So observations with long exposure times or several observations taken together (like those for 3-Colour images) might take longer to get observed.

Priority

Ideally, all requests for observations would be taken, but there are so many things that nobody has any control over (from bad weather to unexpected but exciting things like exploding stars) that it is impossible to guarantee that. To help the telescope decide which are the most important to finish, all requests are given a "priority".

For research astronomers, the priority is decided by a committee who think about what all the astronomers who are using the telescope want to do, and which are the most exciting or important.

For observations sent through The Schools' Observatory, we use the priority to both boost observations that a lot of people want to get done, and give people who have not used the telescope much a bigger chance of getting their first observations done quickly. However, this is only used together with all the other factors - lower priority observations might still be done first if all of the other conditions are better for them.

What to do once your observation is available

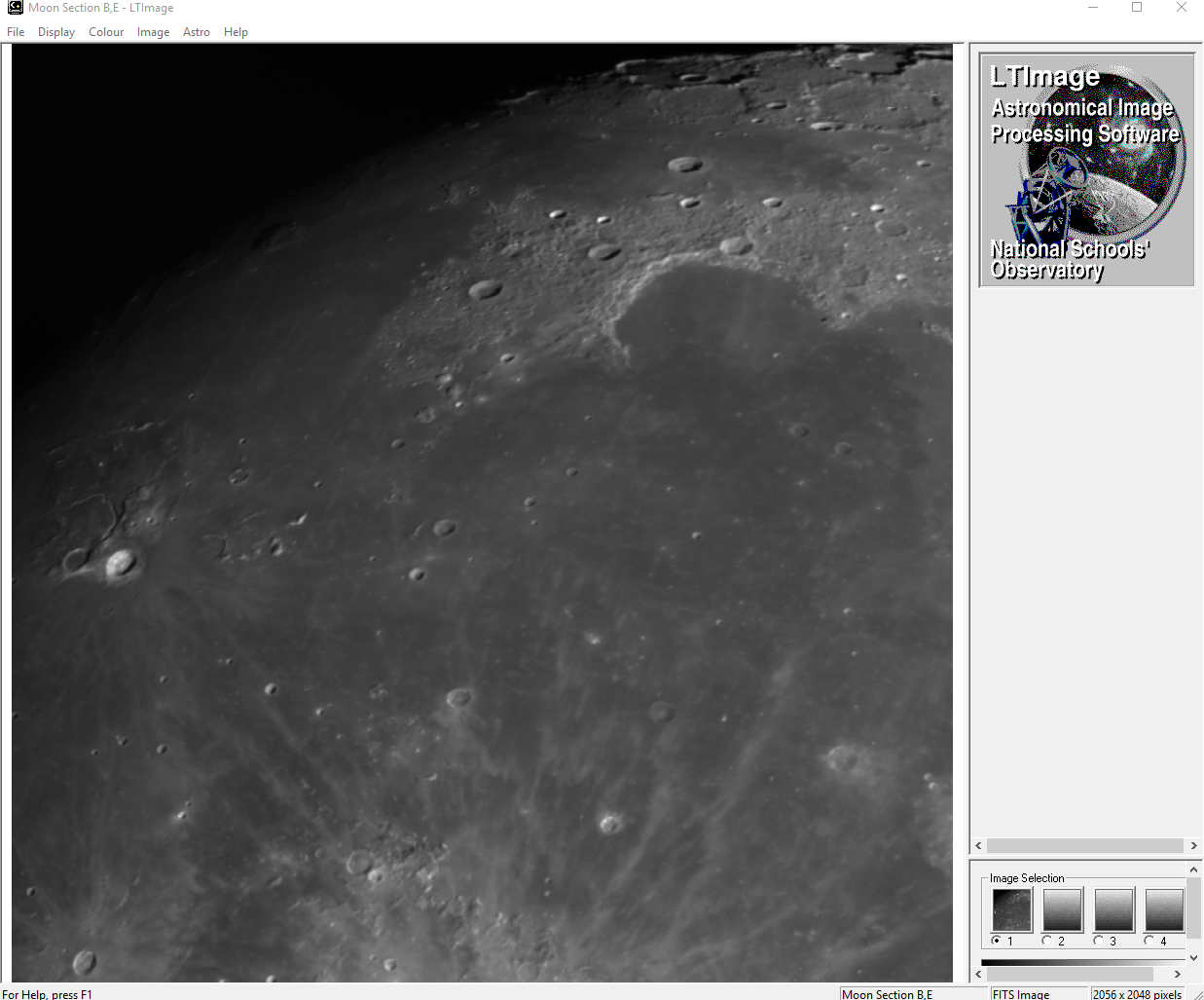

Once your observation has been taken and is available, you will get a message on your "My Observations" page. Click on the Code number and follow the instructions to download the image data.

You can then use The Schools' Observatory software to display, explore and analyse the data. This software, like Go Observing itself brings the power of professional astronomy tools into the classroom in a much more "user-friendly" way. You can find out more about what the software can do by following the help videos or simply loading in some data and playing!

In addition to the image data itself, you can also get a lot of additional information when you download your image. These include information about the weather and observing conditions. Not only are these interesting in their own right but can help you to understand any differences between observations (Was there any thin cloud? How close was the moon? etc).

What to do if your observation was not completed

The simplest thing to do it to try again! If you are sure that the observation is exactly what you want, just go to your list of observations and click on the button.

However, if your observation was hard for the telescope to take the first time, it could be just as hard now, so you might want to try something a bit different. In which case, go back to Go Observing and see what you might change. For example, you might find a similar object that is easier for the telescope to fit in (check the coloured "Observability" bars). Or you may want to get a single-colour observation rather than a 3-colour one.